The January news from way back: seems that not much has changed

East Falls NOW, January 2024, by Wendy Moody and Steven Peitzman

Following is a sampling of news reported in East Falls newspapers during Januarys past. The popular local papers were the Weekly Forecast, the Record, and the Suburban Press. To learn more about these past local newspapers, join the EFHS for a zoom lecture on “Old East Falls Newspapers” on February 28, 2024 at 7pm (details will be found on the EFHS website).

These three extracts reinforce that not much has changed over the years: a complaint of inadequate police presence, the challenges of women in the workforce, and the need for private contributions when the local government cannot provide funds.

January 24, 1901 – Our Police Protection – Although there has been an increase in the number of police patrolling the large territory included in the district of the substation at the Falls, the force in toto includes nine patrolmen. What is termed one beat takes in as much territory as is comprised in the new Thirty-First District, which has some 30 odd officers, yet this District – beg pardon “beat” – is protected during the entire day by one solitary officer who does a tour of 12 hour duty. At night the tour is divided into two shifts…the officers are mounted, but just consider a man on horseback for twelve consecutive hours… Is this the kind of protection our people are paying taxes for…in a district numbering 10,000 souls? The force is utterly inadequate and our business people should demand that we be given the protection which the extent of such a district requires. Weekly Forecast (We are not sure what sorts of crimes or other troublesome activities were prevalent in East Falls in the late 1890s. Strikes at Dobson Mills certainly did occur in this period.)

January 12, 1930 – Three quarters of a century ago, Hannah E. Longshore, M.D., the first woman physician here, drew a raucous crowd when she hung out her shingle. The crowd expressed its contempt. “A ‘she’ doctor!” The expression summed up the opinion of an age intolerant of all feminine endeavor…she was ignored, condemned, sneered at. Druggists refused to fill her prescriptions. Despite insults and handicaps, Dr. Longshore went quietly about her work of healing. Then the tide inevitably turned. She won the love and respect of the public that had condemned her and even established a lucrative practice. Dr. Longshore was one of the first eight graduates of the Woman’s Medical College. Record (The “first woman physician here?” We don’t recall seeing any references to Dr. Longshore practicing medicine — or living – in the Falls, but she was a celebrated Philadelphian who attended the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania long before it moved to East Falls.)

January 18, 1934 – Trustees of the Old Academy held their quarterly meeting last Monday night. Despite the fact that the city has failed to provide the residents of Falls of Schuylkill with a recreation center, the people of “the Falls” can point with great pride to the fact that on Indian Queen Lane stands the oldest community center in Philadelphia. Old Academy was paid for by contributions made directly by the men and women who lived in its vicinity. It was erected by William Moore Smith, a son of Dr. William Smith, first provost of the University of Pennsylvania – and his wife, Ann, in the year 1816 and completed in 1819. The provisions distinctly stated that the building should be used for recreation, education and worship. There was a clause that if the Trustees failed to meet in January of any year the land would revert to the donors, or their heirs. Suburban Press (Of interest, by 1932 the Old Academy had become the home of the much respected Old Academy Players. The trustees of the building were long known as the Falls of Schuylkill Association.)

A Presidents’ Month anecdote: no Falls monument for a slain president

East Falls NOW, February 2024, Wendy Moody

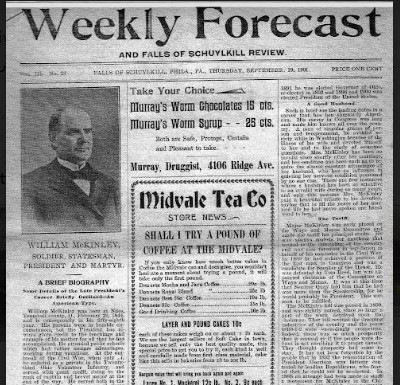

The assassination of our 25th President, William McKinley, created an awkward moment in East Falls history. Recall that McKinley took office in 1897, with his tenure highlighted by the Spanish-American War and increased tariffs.

Days after his assassination (Sept. 14, 1901) at age 58, our local paper, the Weekly Forecast and Falls of Schuylkill Review featured a tribute to McKinley announcing the McKinley Memorial Monument Fund – a drive for the erection in the Falls of a monument to the late president. This endeavor revealed a surprising lack of enthusiasm from our residents and led to weekly “scoldings” by the newspaper.

As you read these excerpts, keep in mind that they are abridgements of long weekly rants:

Oct. 10, 1901:

“Two weeks ago, the Forecast published a letter advocating a memorial to McKinley in our vicinity and volunteering to act as treasurer. Since that time, two donations, totaling $15, have been received, both from local organizations. Is this a true reflection of the people of Falls of Schuylkill? We trust not. How humiliating it is to realize that we have not received one individual donation! We trust the delay is not indifference, but simply neglect….. As a tribute to a beloved President, through whose administration our nation has prospered, and whose life was a beautiful example of morality, marital felicity, and respect, who can say but these ennobling traits may be a guiding star for generations yet unborn, as they are read by the passerby (on a monument), whether it be impressed on cold stone or emblazoned brass.”

Oct. 17, 1901:

“Nothing is more disagreeable … than to bring another to task for failing to fulfill a duty; yet this is the unpleasant position the Forecast finds itself in by the neglect of its readers to respond to its local fund for a memorial to our late President…. It is indeed gratifying to add a few additional names (three donations of $1 each) and the Forecast is thankful for the example set by them…. It is utterly impossible to offer any excuse for the lack of interest manifested by the people of the Falls. If they have no patriotism, they should at least have a certain amount of local pride….”

Oct. 24, 1901:

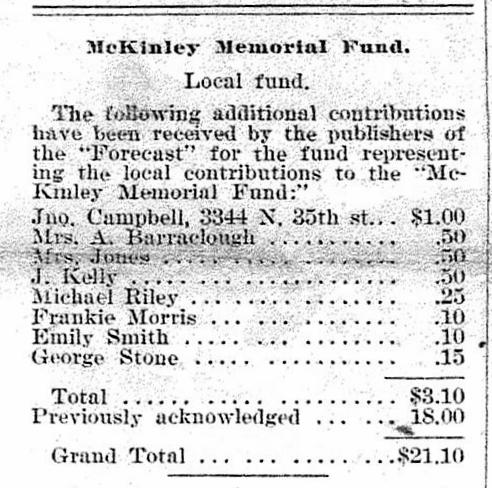

The Forecast published periodic lists of donors, such as that shown in the photograph. But then…

Oct. 31, 1901

“Since last week, not one cent additional has been received. It is utterly useless for the Forecast to express its opinion of the indifference so strikingly manifested by our residents…. everyone should feel the deep humiliation which their want of interest has cast upon the entire community…. Our business men are too deeply engrossed in their own selfishness to spare even 10 cents in grateful remembrance of a man to whom they owe the greater part of their prosperity…. The Forecast made continued effort to interest its readers in this movement. Its failure is the fault of the local residents. It will not further humble or belittle [McKinley’s] greatness by appealing to a penurious public who have clearly shown they have neither patriotism nor local pride enough to assist in this movement….. Unless the public show a different disposition before the next issue, the Forecast will close the fund and turn the money over to the general fund for the erection of a Philadelphia memorial.”

Nov. 7, 1901

“The local fund … is now closed, there having been no additional subscription received during the last week…. The $21.10 will be sent to the city-wide fund. The Forecast will be pleased to assist in any further interest in the proposed memorial. Let some of our public spirited Falls citizens take the matter in hand.”

Added Notes: In 1908, a bronze on granite 9’6” sculpture of McKinley was erected at the South Plaza of City Hall. A financial depression afflicted Americans in the 1890s, so Fallsers might still have been watching expenditures in 1901. Also, the turbulent early years of the 1900s saw several strikes at the Dobson Mills. The Dobsons, at least, would have favored McKinley, being staunch protectionists, but their names do not appear among the few Falls donors.

Remembered in Women’s History Month: Elizabeth Fleisher, East Falls architect

East Falls NOW, March 2024, Steven J. Peitzman

Born in 1892 into a prominent German-Jewish family of Philadelphia, Elizabeth R. Hirsh attended Philadelphia High School for Girls and then Wellesley College, where she graduated in 1914 as a Phi Beta Kappa. She looked to a medical career. But after marrying Horace Fleisher (of the Fleisher yarns and hosiery companies) in 1916 both decided to pursue training in architecture, and they moved to Boston. Horace gained admission to Harvard’s program in landscape architecture, but the school did not admit women. Elizabeth instead attended the Cambridge School of Architectural and Landscape Design for Women, then associated with Smith College, and completed its program in 1929. Possibly her experience with this unusual single-sex school (created and taught by supportive men) helped kindle interest years later in the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

The Fleishers returned to Philadelphia to practice their newly acquired professions. Elizabeth entered into a partnership with Gabriel Roth in 1941 that lasted until her retirement in 1968. Along the way, she and her husband raised three daughters! Her most prominent and admired project with Roth is Parkway House (1952), the large ziggurat-like building at 22nd Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, whose U-shape seems to embrace and welcome the Parkway and Philadelphia Museum of Art. It remains one of Philadelphia’s distinguished residential edifices.

But where are the connections of Elizabeth Fleisher with East Falls? Two, not surprisingly, are buildings. The modernist former “Ann Preston Hall” section of the Woman’s Medical College/Medical College of Pennsylvania (now part of Falls Center) stands as a product of the Roth and Fleisher office, though its primary designer was Thaddeus Longstreth, then working with the company (1950). Even if a project is not primarily designed by the heads of an architectural firm, it emerges within a team; and the principals must approve before drawings go from studio to the work site. The second building is the former home of the Fleishers, who for some years lived in the Falls. “Tulipwood,” at 4030 Apalogen Road, was designed by Fleisher and built in 1954. It is one among a remarkable colony of modernist dwellings along Apalogen and nearby.

One more connection of architect Fleisher with East Falls returns this story to the Woman’s Medical College. There (and into its coeducational years as MCP, the Medical College of Pennsylvania) she served on the Board of Corporators for thirty-three years, “giving generously of her time, her ideas and her talents.” The board minutes noting her death in June of 1975 went on to recognize her as “Deeply interested in the education of women…[who] in her own architectural career served as a model for young women entering medicine.”

Take a walk around Apalogen Road to view the modern houses, and another to the Indian Queen Lane entrance of Falls Center to look at part of Ann Preston Hall. Leaf-less winter is the best time to gaze at architecture.

Thanks to Matt Herbison at the Drexel College of Medicine Archives for his help. Our newly rebuilt website is eastfallshistoricalsociety.org. Reach us on email at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join – you can do so easily on our website.

Historical Society offers walking tour of The Oak Road

East Falls NOW, April 2024

What is the story behind The Oak Road, an anomalous one-block street winding “off the grid” from School House Lane to Midvale Avenue, whose proper name requires “The,” and which features a small island with an oak tree?

The street and its dominant dwelling, the “Timmons House,” were created by Henry W. Brown in 1906-1907.

Brown was a prominent figure in the insurance industry and a lead player at the Germantown Cricket Club. The Oak Road came to be both a residential “colony” for the Brown family and a handsome development of mostly Colonial Revival homes.

The East Falls Historical Society will offer an architectural-historical walking tour along this pleasant Street on April 20, 2024.

Other buildings on the tour will include the “Ivy Cottage,” a Gothic revival house dating to circa 1860, and the beautiful Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd, designed by Philadelphia architect Carl Ziegler and built in 1926.

The walkers will also learn about two nearby historic buildings on School House Lane. All told, six structures on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places will be described by tour leaders Steven Peitzman and Nancy Pontone.

The tour meets Saturday, April 20, at 10:00 a.m. at the southwest corner of School House Lane and The Oak Road. The fee is $15, or $10 for EFHS members, paid on-site. Registration is not required. The tour goes unless there is steady rain.

April, continued

Highlighting the ‘East Falls’ in Jefferson-East Falls

East Falls NOW April 2024, by Rich Lampert

About a year ago, East Falls Historical Society announced that we are aiming to develop an online encyclopedia of East Falls history, eventually encompassing all the key people, institutions, buildings, and more that have defined our community since it was first settled by Europeans in the mid-1600’s.

This is a big job – bigger than East Falls Historical Society can accomplish on our own. We’ve been looking for partner organizations that might be able to amplify our efforts, and in recent months we’ve embarked on a promising effort with Jefferson University-East Falls. The platform for our collaboration is a course entitled Uncovering the Past: Tools, Methods, Strategies, a foundational course in Jefferson’s Historical Preservation graduate program taught by Prof. David Breiner. In this course, students track down data using written, graphic, and oral sources. Field trips to archival repositories are a key activity, and students also learn how to conduct oral history interviews.

Last winter, East Falls Historical Society asked Prof. Breiner if he would be willing to assign some East Falls-oriented research topics to his students during the current academic term. Not only did he agree to this, he also invited active participation from our members.

In the weeks before the term started, we collaborated with Prof. Breiner on selecting research topics. We uncovered a common interest in learning more about building that haven’t yet been well documented through listings in the Philadelphia or National Register of Historic Places (for instance, the Kelly house on Henry Avenue), or the National Historic Engineering Survey (for instance, the Falls Bridge.) We came up with an intriguing list. In alphabetical order, they include:

- 3333 West Hunting Park Avenue, near Ridge, a former industrial building that is now an office for State Rep. Roni Green

- Abbottsford Homes and community building, the landmark on lower Henry Avenue

- America Hall, the three-story structure at Sunnyside and Conrad Streets with a row of storefronts on the first floor

- The BINAC/UNIVAC birthplace, on Ridge Avenue across from Laurel Hill Cemetery

- “The Button,” the clubhouse for Bachelor’s Boat Club, along Kelly Drive

- The “Chemical Building” on Fox Street, the multi-story building within the Queen Lane water treatment facility

- Falls Methodist Episcopal Church on Indian Queen Lane, now an office building

- The fire station, an interesting midcentury modern structure, especially when seen from the Kelly Drive side

In addition to helping Prof. Breiner choose research topics, East Falls Historical Society is providing his students with our perspective on our community’s history. EFHS president Steve Peitzman presented an illustrated overview of East Falls history to an early class session, and in early March the students conducted one-on-one oral history interviews with several of our members to uncover perspectives about specific buildings as well as our recollections about life in East Falls. And we’re invited to join in a class session in late April where students will present the results of their research.

The students’ written papers may provide the greatest benefit to EFHS activities. The papers will be written in the form of nominations to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, so they could form the basis for formal nominations that EFHS could take to the City Planning Commission. In addition, we hope that the information in these student papers will be the foundations for articles that we can develop for the online encyclopedia.

We’re enjoying working across the town-gown gap with Prof. Breiner and his students, and we’re pleased that our 2026 ambitions are helping to reinforce the “East Falls” in Jefferson University -East Falls. And we hope this is the first of many collaborations that will benefit EFHS, in particular our ambitious online encyclopedia project.

Elizabeth Sorber was the very busy midwife of the Falls of Schuylkill

East Falls NOW May 2024, by Clare McCabe

Elizabeth Sorber was a midwife in the Falls of Schuylkill in the early nineteenth century. She kept a record of the deliveries she attended in a memorandum, or receipt book, which survives today in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The memorandum book records the last name of each mother, the gender of the new baby, and what Sorber charged each patient for the delivery.

The book records deliveries from 1814- 1831. Sorber might have kept practicing after 1831, but if she did, those records are lost to historians.

Over the course of 17 years, Elizabeth Sorber recorded 281 deliveries for an average of 15 babies each year. In 1814, her busiest year, she delivered 29 children!

In this time period, East Falls was a relatively small and tight-knit community. Most of her patients were her neighbors.

Her book demonstrates the trust her neighbors placed in her. Almost 40% of her deliveries were from repeat customers, and she attended entire extended families: the Shronks, an early East Falls family, appear 13 times in the book.

Calling Sorber for a delivery was cheaper than calling a doctor. Sorber’s prices ranged from 50¢ to $2.00. In 1824, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia decided that for standard births, doctors should charge anywhere from $8-20.

In East Falls, Sorber probably didn’t have much competition from doctors, as the neighborhood was still fairly secluded. But Philadelphia was the center of American medicine in the early 1800s, and the University of Pennsylvania, the country’s first medical school, had offered courses in “midwifery” since 1765.

In 1819, forty-two doctors listed themselves as “man-midwives” in Philadelphia directories, and more and more general doctors integrated deliveries into their regular practices.

By the first half of the nineteenth century, midwives faced increasing competition from doctors. Even in East Falls, it is remarkable that Elizabeth Sorber continued practicing for as long as she did.

Childbirth in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century was a communal event. Most women gave birth at home, and in the lying-in chamber, as it was called, the pregnant woman’s female friends and family came and assisted her.

Midwives were an important part of this landscape, and often sat with women in labor for days.

After giving birth, new mothers rested in bed, sometimes for weeks, while female relatives took over the new mom’s household responsibilities.

Elizabeth Sorber was no stranger to family in the birthing room. She delivered twenty of her own grandchildren over the course of twelve years. She attended two of her daughters-in-law, Sarah and Mary Sorber, fourteen times, and her own daughter, Elizabeth Morrison, six times.

The entire Sorber family was active in the East Falls community. Elizabeth’s husband, Joseph, was one of the founding trustees of the Falls of Schuylkill Association, who in 1819 raised money for the construction of what is now the Old Academy building.

Her sons also served as trustees, and one of her sons, William, served as the Association’s secretary for years. Several generations of Sorbers conducted a carriage factory at Ridge and Indian Queen Lane.

EFHS and the East Falls NOW are pleased to focus on one of the Sorber women, an evidently skilled and trusted practitioner.

Clare McCabe is a graduate student in history at Temple University, and a native Fallser, though now living closer to the university.

The Bathey Bath House of East Falls – long before air conditioning

East Falls NOW, June 2024, Rich Lampert

If it doesn’t feel like Summer yet, we all know it will any day now. In 2024, most Fallsers will turn on the air conditioning and complain about the weather while sitting in 70-degree comfort. It wasn’t always that way, of course. Long before air conditioning came to East Falls, both kids and adults cooled off at their community swimming pool, the Bathey Bath House.

The surviving head house of the Bathey, which contained the changing room and lockers, is now part of the eatery Breakfast Boutique, located under the Twin Bridges just off Kelly Drive.

The head house and pool (basically, the area under the footprint of Breakfast Boutique’s dining room) were built in 1926, at a cost of $34,164. The architect, Ralph E. White, had an active practice in the Philadelphia area, appropriately including commissions at country clubs including Seaview Country Club outside Atlantic City and various buildings at the Philadelphia Country Club. “The rounded arches above the windows and door tag the Romanesque Style, and recall for us Roman baths and even aquaducts.

City records indicate that the construction bids for the Bathey were accepted in July, 1926, so we assume that the pool opened for swimming in time for the 1927 season. Anyone who lived in the Falls through the 1950’s recalls the place vividly, and the Bathey is mentioned in at least 24 of the oral histories on the EFHS website.

Here’s a small sample of quotations from our oral histories:

Bob Furlong: “I was lifeguard there in 1949. The pool was drained every night and had fresh water daily. It was open six days a week, with girls and boys alternating days. The swim would last an hour, and when the whistle blew, everyone left. Because you needed a dry suit to get in, some kids put their wet suits on the trolley tracks (#61 on Ridge) to dry them under the trolley wheels. I remember guys diving off the high wall into the pool – dangerous, but fun.”

Jean Rowland: “A man opened the Bathey in the morning for you to go in. They only had 10 places to change into your bathing suit, so if you wanted one of them, you’d be there 6 a.m. waiting outside. We wanted to make sure we got a locker, because we’d be embarrassed, I guess. They had a lady who taught us to swim. That was nice.”

Inez Ierardi Fletcher: “We went during the summer every chance we had. You could go for an hour and then they’d let you stay if you dried off your bathing suit and it was somewhat dry and you waited the hour in the little fitting room and then you could go back in again…(T)here were women who were lifeguards and they would look you over and be sure you had no sores and you were clean. They were extremely careful.”

While Fallsers loved the Bathey, it closed in 1958, superseded by the much larger pool complex at Gustine Lake a few blocks away.

The pool was filled in, and the head house structure sat, vacant and derelict, for 50 years. Finally, In 2007, the Fairmount Park Historical Trust and East Falls Development Corporation facilitated a public-private partnership with developer Brinton Partners. In 2009, Brinton leased the space to Trolley Car Diner owner Ken Weinstein, and after six months of construction the Trolley Car Café opened in June 2010.

Repurposing a historical structure isn’t easy, nor is it cheap. It took a veritable village of government and nonprofit organizations to fund the project. Funders included the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the William Penn Foundation, the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, the Schuylkill River Heritage Area, The Schuylkill Project, City of Philadelphia Commerce Department, The Reinvestment Fund, The Merchant’s Fund and capital investments from Brinton Partners and Trolley Car Cafe.

Whether or not longtime Fallsers enjoy some Eggs Hollandaise along the river, the restored Bathey headhouse will continue to elicit happy and cooling memories.

Next month, we’ll discuss the briefer but more fraught history of the pool complex at Gustine Lake.

Gustine Lake: from an old swimming hole to a public swimming pool to … history

East Falls NOW July 2024, by Rich Lampert

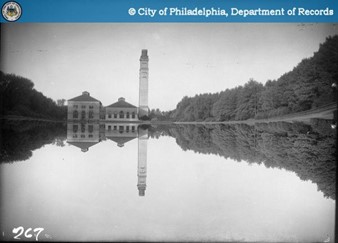

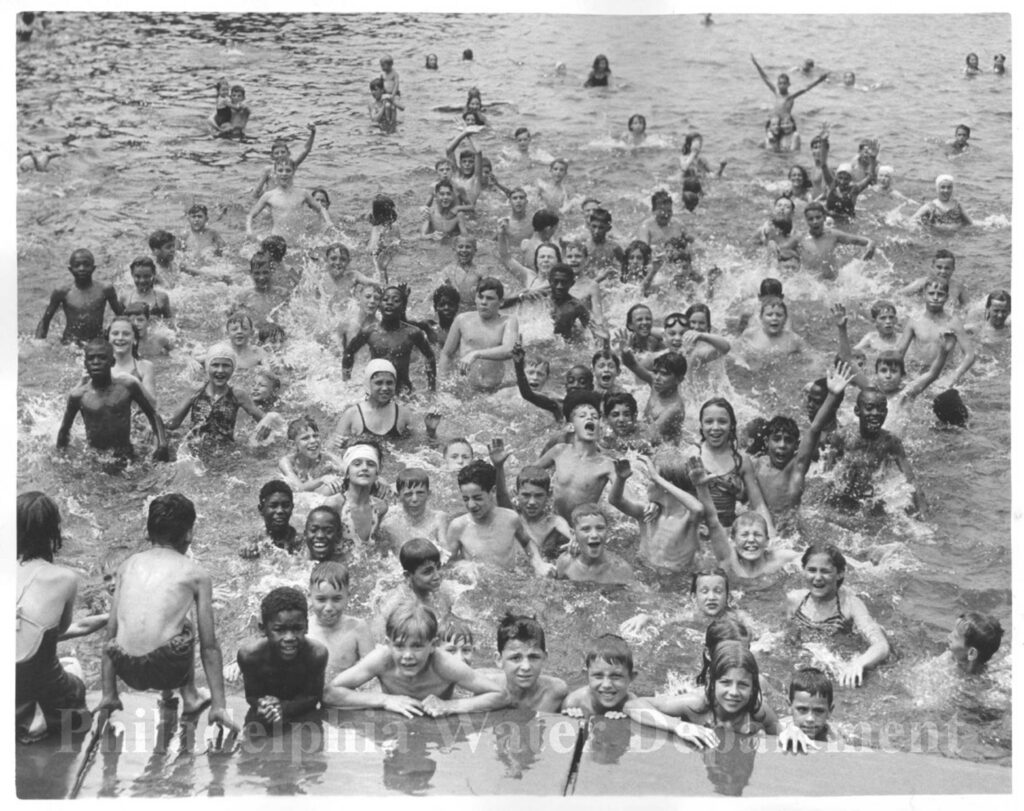

Last month’s column from East Falls Historical Society talked about the storied Bathey swimming pool, vividly recalled as a center of East Falls summers until it closed following the 1958 season. The successor to the Bathey was a public pool complex at Gustine Lake, a name that now exists only on antique maps. What was the area of Gustine Lake is now covered by the Legacy Tennis Center and the Gustine Lake Recreation Center along Ridge Avenue.

Swimming at Gustine Lake actually started even before the Bathey was built; there are newspaper accounts of Gustine Lake as both a swimming site and a place for ice skating appearing in the Philadelphia Inquirer as far back as 1902. The “lake” – actually a man-made concrete splash pool about three feet deep – ran parallel to Ridge Avenue for about a quarter of a mile (400-plus yards!) and, according to newspaper accounts, attracted up to “thousands” of kids at a time. As far as we can tell, typically just one lifeguard plus an additional person who could provide first aid were on duty. In contrast to the two dozen or so recollections of the Bathey in the oral history collection of the East Falls Historical Society, Gustine Lake is mentioned by only a handful of people, almost always as a place for ice skating rather than as a place to swim. (The one mention of swimming in Gustine Lake recalls sourly that kids were likely to cut their feet on broken glass, a complaint echoed in newspaper articles going back to the 1930’s.)

Because the “lake” was fed directly with water from the Schuylkill River, swimmers also faced increasing pollution. In 1954, Fairmount Park Commission had to seek an emergency allocation of $100,000 to “recondition” the place.

Although the written history isn’t clear, the condition of the “lake” apparently led the Fairmount Park Commission to develop a brand-new, formal swimming pool. Archival photographs at water.phila.gov/history document opening ceremonies in 1965. Gustine Lake became one of just four pools run by Fairmount Park Commission, joining others in West Fairmount Park, Hunting Park, and FDR Park. (Philadelphia’s Department of Recreation ran its own pool system, with more than 80 pools all over the city.)

Around the time that the new Gustine Lake pool opened, public pools around the country were encountering social challenges, discussed in detail by Jeff Wiltse, a professor of history at University of Montana, in a book called Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in North America. In an interview on WNPR, the NPR station in Connecticut, Prof. Wiltse described a trend that probably challenged Gustine Lake and most other public pools around Philadelphia:

Racial desegregation of pools began in the 1940s and continued to the 1960s. In the south, cities just closed their public pools instead of allowing mixed race use. In many southern cities, there were literally no public pools. In the north, the response was more nuanced. When a pool that was previously for whites only became racially desegregated, white swimmers en masse abandoned it. I found case after case that white attendance would drop 90-95 percent when black swimmers started using it.

Overall usage of these large resort pools started to attract fewer swimmers so cities stopped investing money in them. Over the course of a few years, these pools became dilapidated, they required significant maintenance, cities simply refused to pay the cost of rebuilding them, and [they] ended up closing down.

Sometime in the early 1990’s (we couldn’t uncover specific documentation), officials discovered that the Gustine Lake pool was leaking, and determined that the costs to address the leaks would be prohibitive. And that was the end of Gustine Lake. The community discussions about redevelopment were intense and sometimes contentious. Although it drew from several neighborhoods, few if any voices were raised in favor of reviving the swimming pool. Unlike the Bathey, Gustine Lake pool had never quite won the hearts of East Falls residents, and it passed quietly from our memory.

August – no column

September

Back to School at Forest and Breck

East Falls NOW September 2024 by Wendy Moody, Steven Peitzman, Joe Terry

“Back to school” does not come as a happy sound to most kids, and probably never has. In this article, we are going way back to school, to learn about the schools Fallsers attended before the opening of the Mifflin School in 1936. There was in effect one Philadelphia public school–but two names–and three buildings. Of course, many children attended St. Bridget’s school.

Free public education began in Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania, when the state legislature in 1818 established a school district in Philadelphia for poor children to be organized and overseen by a Board of Controllers. Its first head “controller” was Roberts Vaux, of the same family which produced a mayor—hence, Vaux Street. In 1837, the free school system was opened to all children, not just the poor, but it long remained segregated. Not until 1895 was compulsory attendance required. Many boys and girls were, of course, working in mills or other jobs. Just about the same time the Commonwealth first acted to enable public education (1818), residents of the Falls built the Falls [later “Old”] Academy (1819) to serve as school, church, and meeting hall.

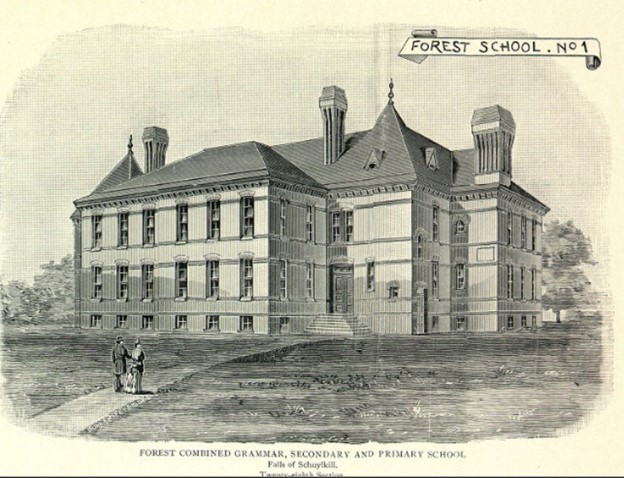

The photograph labeled as figure 1 is from the Charles K. Mills Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This image shows the two early buildings of the Forest School near the (former) intersection of Krail and Crawford Streets.

The older building (1850) is of the Italianate “villa” style. The architect is not known. The surfaces are likely stucco over stone, and if the stucco was yellow, this was the yellow school building mentioned in various memoirs. As Falls of Schuylkill grew so did the number of kids going to school. Thanks to funding from city council in 1865, a burst of school construction occurred in 1866-1867, including the eight-room stone building seen on the left, designed by architect Isaac Hobbs, and shown more clearly in figure 2.

But in 1875 the school system had to lease part of the Falls Academy for overflow. Another unexpected flow of money for schools occurred in the mid-1880s, and again the Falls of Schuylkill benefitted, with the largest and grandest edifice so far (though any remembering it as children in its last years may not agree). The 1850 school was demolished, and the red brick building designed by school architect Joseph Anshutz took its place in 1886 (figure 3).

The 1866-1867 two-story stone building was retained, and housed the early grades. In 1913, the Board decided to change the name of the school from Forest to Breck, for Samuel Breck, an early nineteenth-century legislator, school board member, and abolitionist. At least one of us (SJP) has to admit to having no idea who Forest was, or even his first name. So the 1886 building was Forest when built, then Breck as of 1913. Although coursework of course changed along with grades supported, administratively there was one public school, Forest/Breck. The structures were demolished when the US 1 expressway was built, joining many lost East Falls buildings.

We will now move on from the buildings to recollections of schooldays within, compiled by Wendy from some of our oral histories (not “fact-checked”).

Louise Halstead (b. 1882) went to Forest School until age thirteen, then worked in Dobson Mills as a burler. She remembers: And we had two schools, we had a little school and a big school. The little school ran to the 5th grade, and then you went to the big school and you go to the 12th grade, and from there, if you were lucky, you’d go downtown and finish your education down there. Yea, we all had favorite teachers, but they were, they didn’t put up with much foolishness, as they do today. They give you a couple of raps on your fingers and that would be it. And they had a stick, a ‘pointer’ they’d call it, and it was about this long and they’d go around with that, you know, pointing to the blackboards… When I went, we learned off our blackboards – it was written there for us and then we learned from there.

Mary Webster (b. c.1910) recalls some teachers and one principal at Forest School:. She used to wear a little shawl around her, oh she was an old maid. Typical old maid. And she had first grade, Miss Walker – I don’t know her first name – she had one first grade, and she had the other. And then there was Carrie Dyson. Her father had a junk store down on the Ridge, and you could get nice things down there, you know, cheap. Then there was an old, old man with a beard, and his, I think his name was Dr. Samuels [principal?], and he was kind of cute. Laughs. He used to kid around with the kids a little bit, nice, you know, real nice.

Jean Buckley (b. 1920) recalls Breck School in the 1920s: Oh I just loved it! We walked to school. We had to be there by 9am and lined up in lines, you know. I used to walk into the classroom, and we walked home at twelve o’clock for lunch. We had to be back by 1:30, walk back. And we used to have a little Italian man who sold pretzels, salt pretzels… We had some great teachers. We really did. I loved that little school.

Edi Gotwols (b. 1921) shows a good memory for teachers: I remember all the ones – Ms. Kaid, Mrs. Wertz, Mrs. Toppen, Ms. Edwards taught math. Oh yeah it was okay, it was close to home.

Shirley Shronk (b. 1926): I went to the Breck School in the little old stone building for kindergarten and went through 2nd grade. For third grade we went to the brick building. There were nice little seats where we would go to sit for recess and a stone bench where we could sit and chat with a friend. There was no water in the stone building. If you wanted to use the bathroom, you had to go to the brick building.

Our newly rebuilt website is eastfallshistoricalsociety.org. Reach us on email at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. We welcome any recollections of schooling in East Falls in the 1930s perhaps heard from your parents. Also, any information about the East Falls Falcons football team of the 1940s. And join – you can do so easily on our website.

JOHN B. KELLY AND PHYSICAL FITNESS: A TALE OF TWO PARTIES

East Falls NOW October 2024, Rich Lampert for the East Falls Historical Society

According to the bylaws of the East Falls Historical Society, one of our purposes is “to provide reference service for historical queries about East Falls.” As we dig for answers, we sometimes find ourselves going down rabbit holes in what we thought was very familiar ground – in this case, the life of John B. Kelly, the patriarch of the most famous family in East Falls.

Our ace researcher Joe Terry fielded a query about a rumor that President Franklin Roosevelt once had dinner at the Kelly house on Henry Avenue. Joe couldn’t confirm that, but he did uncover a prominent role that Kelly once had in the FDR administration. Farther down the rabbit hole, we discovered that Kelly had a somewhat similar role in the Eisenhower administration. Since we’re in the middle of a polarized election season, it’s refreshing to revisit a generation when presidents of both parties could look to the same person for advice.

John B. Kelly was not only a two-time Olympic rowing medalist, but he was also something of an idealist. The book Kelly: A Father, A Son, An American Quest by Daniel Boyne describes how Kelly founded the modern Democratic Party in Philadelphia after learning that the so-called Democratic Party of the early 1930’s was actually a puppet organization funded by the Republican machine. Candidates running on Kelly’s new “Independent Democratic Party” ticket in 1933 won elections for City Treasurer and City Comptroller, taking control of city finances out of the hands of the Republican machine, at least for the time being. Kelly, apparently over the objections of his wife Margaret, ran for Mayor in 1935 but lost — albeit with almost 10 times the number of votes the Democratic candidate had received in the previous election. That was Kelly’s last run for elective office, but he stayed on as chairman of the Democratic City Committee for decades.

Kelly also turned his idealism to physical fitness, and the historic research rabbit hole opened up in the form of newspaper articles from around the country. Kelly started writing newspaper columns in 1937 about the need to improve the physical fitness of Americans with the possibility of war on the horizon. According to Boyne’s book, in 1938, when FDR came through Philadelphia on a campaign tour, Kelly sat next to him at a banquet – not on Henry Avenue, but somewhere in Center City. Almost surely Kelly talked to FDR about physical fitness. In 1940, FDR encouraged Kelly to travel around the country to make speeches promoting physical fitness as a national concern. Then, in 1941, FDR put him in charge of a newly created Physical Fitness Division in the Office of Civil Defense.

Kelly developed this program with his characteristic vigor, with a particular focus on ensuring that American industry could supply the necessary sports and fitness equipment in a wartime economy. In all, Kelly appointed 62 volunteer coordinators for a vast array of activities, among them archery, bag punching, baseball, canoeing, fencing, field hockey, and even trap shooting.

To conservatives of all stripes, this looked a lot like government waste. In March 1942, Sen. Harry Byrd, a segregationist Democrat, criticized what he saw as a commercial tinge to the program and claimed (falsely) that the coordinators were being paid. Kelly persisted, and at FDR’s urging he undertook a national speaking tour in 1944, albeit with mixed effects on public opinion. In the fall of 1944, a syndicated column criticizing Kelly’s program as a plot “to weld the nation into a huge 4-H club” ran in newspapers in El Paso, Texas; Cincinnati, Ohio; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and possibly others. The tart response to Kelly’s efforts, undertaken as part of wartime mobilization, reminds us that even seemingly uncontroversial programs can receive a full share of politically motivated criticism.

With the end of World War II, Kelly’s program disbanded. However, Kelly’s interest in physical fitness didn’t wane, nor did the nation’s. There was a national uproar in 1955 when researchers revealed that some 56.6% of children failed a then-authoritative test of physical fitness. Kelly, still a prominent political figure at the top of the resurgent Democratic Party in Philadelphia, was able to get in touch with President Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican. Eisenhower was receptive to his concerns. As a top general in World War II, Eisenhower had heard more than enough about the poor physical conditioning of draftees. With Kelly’s urging, he eventually issued an executive order in July 1956, establishing the President’s Council on Youth Fitness.

Kelly and other physical fitness advocates attended the so-called Vice President’s Conference on Fitness of American Youth later in 1956, meaning that Kelly, who had organized the party that deposed the Republican Party from control of Philadelphia, was presumably in the same room as Richard Nixon, one of the most partisan Republicans of that generation. Apparently, both men could set aside their political differences when they had common concerns.

As Boyne recounts in his book, the Eisenhower Administration failed to make physical fitness a high priority, so nothing tangible resulted from Eisenhower’s executive order. Kelly passed away in June 1960, too soon to see John F. Kennedy, who preached and exemplified “vigah,” move into the White House. There’s little doubt, though, that John B. Kelly’s fierce advocacy about physical fitness still echoed for politicians of both parties.

Reach us on email at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. The book about John B. Kelly referred to in this article is Kelly: a father, a son, an American quest by Daniel J. Boyne. Copies are held by the Falls of Schuylkill branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia system, and also at Parkway Central, the Andorra and Coleman (Northwest Regional) branches.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH HOSPITAL TO MODERNIST LIVING: THE TOWER AT HENRY

East Falls NOW November 2024, Nancy Pontone for the East Falls Historical

Society

The American Institute of Architects of Philadelphia sponsored a construction tour of the Tower at Henry on September 6, 2024 attended by architects and engineers but also by four board members of the East Falls Historical Society. The project is the second phase of a larger campus masterplan by senior services provider, NewCourtland, on the site of the former Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute (EPPI). The tour involved climbing 12 stories! New elevators had not yet been installed.

NewCourtland’s first phase at the EPPI site finished in 2019, created 85 one-bedroom and efficiency apartments giving seniors age 62 and older safe, affordable, independent living with supportive services. Max Kent, the Chief Operating Officer of NewCourtland, has generously provided the East Falls Historical Society an office and Grace Kelly exhibition space on the first floor of this structure.

The second phase, the Tower at Henry with 220,000 square feet, will comprise 173 units, of which 40 will be intermixed senior affordable apartments, with the remainder set at market rate. Amenities include a fitness center, game room, and rooftop event spaces. Although unfinished, several apartments of 43 possible layouts, some with outdoor space and two levels, were seen on the tour. Spacious bathrooms, kitchens with tile backsplashes, washer and dryers, high ceilings, sound proof flooring, and large windows with breathtaking views are some of the features. Center City, the Schuylkill River, Fairmount Park, suburban counties and the Queen Lane reservoir are visible from this geographic high point.

EPPI opened in 1956 as a research and training hospital designed to foster advances in understanding and treatment of the mentally ill. The Institute displayed the evolution of mental health facilities from 19th century asylums to modern healthcare facilities in the mid-20th century. Five area medical schools were affiliated with EPPI including neighboring Medical College of Pennsylvania (MCP), the former Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, which managed the site beginning in 1981 until it closed along with MCP Hospital c. 2005.

The Tower at Henry embodies the form and features of the International Style that became one of the most prominent architectural styles for institutional and commercial buildings in the US. Philadelphia is the location of the first International Style skyscraper in the country, the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Building (PSFS), built in 1932. EPPI’s character-defining features of this style as expressed by the architectural firm of Harbeson, Hough, Livingston & Larson, with assistance by architect Harry Sternfeld, include exterior buff brick walls, curtain walls, windows that turn the corner of the building, curved surfaces, spandrel panels, fieldstone accents, concrete columns, and rectangular forms.

Eli Storch, the lead LRK architect on the project, is retaining these features as windows are updated, bricks are restored and panels replaced. Shawn Frawley of Axis Construction troubleshoots inevitable problems that arise, saying he prefers the challenges of restoration to working on new construction.

The team in place is making changes to the interior for its adaptive reuse. Original terrazzo floors in elevator lobbies will be refinished and concrete hallway floors buffed and polished. Glazed tile walls typical of hospitals will be retained. Hall ceilings will be open but painted black to help disguise new electrical and HVAC conduits while keeping the airiness afforded by their height. Large windows are great for the views but will have built in roller blinds for privacy. A mid-century modern era building is getting a contemporary interior update.

Access to the Tower at Henry is in the back where large oak trees have been maintained. Landscaping will offer tenants a parklike setting below the building. One tour taker was so enthused about the building’s offerings that he expressed his desire to move in. Not yet – a late fall opening date has been advertised.

Caroline Slama and Steven Peitzman contributed to this article. Do you have questions about East Falls history, or want to know more? See our growing website at www.eastfallshistoricalsociety.org or contact us at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join! You can do so on our website, eastfallshistoricalsociety.org.

Caption: NewCourtland’s Tower at Henry will offer affordable apartments for seniors and market-rate units, as well as some great views. The building when fully restored will gain recognition as a modernist gem.