The post-World War II era

By the time World War II formally ended in August of 1945, the United States had experienced more than a decade of unprecedented challenges, from the Depression that started with a major collapse of the stock market in 1929, the New Deal effort during the early and mid-1930s to rebuild the economy and construct the modern social safety net, and then a war that had unprecedented impacts on virtually every aspect of American society.

Starting in late 1945 it was clear that Americans were ready to return to “normalcy”, the term first coined by President Warren Harding in the early 1920s – a condition they hadn’t known for nearly a generation. East Falls, with a core of longtime residents as well as institutions that had served the community for many decades, had a keen sense of “normal,” although it felt the effects of broader changes.

Post-war Philadelphia

The former mayor and U. S. Senator Joseph S. Clark, Jr., and his son Dennis J. Clark described a hypothetical view from City Hall tower looking over early postwar Philadelphia as follows:

Looming among the row-house neighborhoods in all directions were the dark-windowed factories and mills that had roared with productive energy for over a century. Set among them were the steeples and domes of the churches that bound the city’s people together in committed congregations.[1]

As we discuss in detail below, this description – the row houses, factories and mills, and churches – fits East Falls beautifully.

Philadelphia was, of course, an old city, having been founded in 1682. In addition, it was suffering under the yoke of a long-established Republican machine. As early as 1903, the muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote, “All our municipal governments are more or less bad. Philadelphia’s is simply the most corrupt and the most contented.”[2] Political descendants (sometimes including family descendants among them) of that corrupted and contented machine still controlled Philadelphia politics.

After World War II ended, the machine came under attack from a combination of patrician military veterans and local technocrats. In 1947, the Pittsburgh native Richardson Dilworth ran for mayor against incumbent Bernard Samuel but lost by 93,000 votes. The assault against the machine succeeded in 1949, with Dilworth becoming city treasurer and Joseph S. Clark, scion of a wealthy Philadelphia family, becoming controller. With Dilworth and Clark overseeing city finances and good-government groups conducting their own investigations, tales of rampant corruption in city government started appearing regularly in newspapers, and the Republican machine tottered. In early 1951, Philadelphia voters approved a new Home Rule City Charter with a “strong mayor” form of government that included a strong system of merit hiring to replace the widespread patronage system under the old charter. In the 1951 election, Clark was elevated to the first “strong mayor” position, and Dilworth became district attorney. When Clark chose to run successfully for the U.S. Senate in 1955, Dilworth succeeded him as mayor.[3]

The reformers were determined to alter not just politics, but also the face of Philadelphia. Two of the most prominent physical efforts were the development of Penn Center and the Schuylkill Expressway.

The development of Penn Center[4] entailed the demolition of the landmark Broad Street Station of the Pennsylvania Railroad, as well as the so-called “Chinese Wall” that ran along Filbert Street from 15th Street to the Schuylkill River. Penn Center, a cluster of tall office buildings, occupied the east portion of the space that had been occupied by the Chinese Wall. The concentration of businesses enhanced Center City as the major employment center, reducing the significance of employment in many neighborhoods, certainly including East Falls.

The new Philadelphia City Planning Commission signed off on plans for the Schuylkill Expressway[5] in 1947, and by the late 1950’s construction had been completed within the city of Philadelphia. Construction of the Roosevelt Expressway, which altered the physical face of East Falls, was – at least for highway engineers – a logical outgrowth. The Roosevelt Expressway is discussed later in this essay.

Established neighborhoods outside Center City were left on their own, to a significant extent. The “dark windowed factories and mills” began to close down, sometimes as a result of winding down wartime military spending and sometimes because owners moved their operations to more modern and efficient structures on the outskirts of the city, the burgeoning suburbs, or even the Southern states, where the spread of air conditioning improved both living and working conditions. In many neighborhoods, workers and their families followed the jobs, as cars and modern highways proliferated in the exuberant post-war economy. In some neighborhoods, the homes of the white workers who had moved were occupied by black families, many of whom had come North – first to escape rampant racism early in the 20th Century, and then to take jobs in defense industries during the 1940s. As the black population increased, the phenomenon of “white flight” led to massive changes in many areas of North, West, and Northwest Philadelphia.

Post-war East Falls

At the end of World War II, East Falls was a mostly self-contained community. Oral histories collected by East Falls Historical Society[6] often mention grocery stores, a large hardware store, butcher shops, tailors, a clothing shop, pharmacies, and plenty of bars and inns for relaxation. Ridge Avenue (including the lower part of Midvale Avenue) and Conrad Street were the principal shopping streets. Department stores in nearby Germantown sold what East Falls merchants didn’t.

At a city-wide level, East Falls – relatively small, bounded on two sides by water – was often assigned uncomfortably to be a small adjunct to a larger community adjoining East Falls. For instance, in the 1960 Comprehensive Plan developed by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, almost all of East Falls is included in an area called “Upper North Philadelphia” in the chapter on residential development. (The rest of East Falls – the portion of East Falls above School House Lane, developed almost entirely after World War II — was included as an awkward, narrow extension of “Germantown-Chestnut Hill”.)[7]

Within its compact boundaries, however, East Falls was a vibrant and complex community in its own right.

Social history

The oral histories compiled by East Falls Historical Society collectively depict East Falls after World War II as a cohesive community, with institutions in common (such as Old Academy Players, the library, and the Bathey swimming pool), community-wide festivities (especially the 4th of July picnic), and diversity within a narrow range (churches of six Protestant denominations as well as one Catholic church.) People shopped for their daily necessities in East Falls and spent much of their leisure time in the area as well.

Churches

Churches abounded. The WPA land use map of 1942[8] showed seven churches – Falls of Schuylkill Presbyterian Church and Grace Chapel Episcopal Church along River Road; St. Bridget Roman Catholic Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church, and Park Congregational Church as one ascended Midvale Avenue; and East Falls Baptist Church and Falls Methodist Episcopal Church ascending historic Indian Queen Lane. The Baptist congregation, near the bottom of Indian Queen Lane, had once conducted baptisms in the Schuylkill River. The Presbyterian church moved from River Road to its current location at Midvale Avenue and Vaux Street in 1945, more than two decades after it had bought the plot of land.[9] One indication about the community-building role of churches was that the churches formed the backbone of the annual East Falls 4th of July parade. Each church assembled its own units and marched in turn up Midvale Avenue to McMichael Park. Once the parade was over, each church held a picnic, occupying individual sectors of McMichael Park and the nearby campus of William Penn Charter School.

Recreation

The Alden Theater at Midvale Avenue and Frederick Street showed movies, including bargain Saturday matinee double features for children. It was demolished in 1969 and replaced with a fast-food outlet, Gino’s.[10]

Old Academy Players, a theater company that attracted some professional actors and directors among the largely amateur company, was a consistent presence, although it did not have the capacity to draw the kind of crowds that attended the Alden. The building housing Old Academy, built in 1819, was the oldest extant building in East Falls and had played many roles in the civic life of the community over its long existence. The Young Men’s Literary Association, across Frederick Street from the Alden Theater, served as a gathering place for young men. While its literary activities are not documented, the oral history from Joe Petrone on the East Falls Historical Society site describes a pool room in the basement, and a hall upstairs where dances took place.

Dobson’s Field was the venue for organized and spontaneous sports activities, and McMichael Park was a quiet spot that served a venue for community picnics, especially associated with the annual 4th of July activities. In 1950, Dobson’s Field was formally renamed in honor of Harry S. McDevitt, a judge on the Court of Common Pleas and a longtime leader of the Police Athletic League and the Junior Baseball Federation who lived in nearby Germantown.[11]

Since the late 1920’s, the Bathey swimming pool was operated by the Philadelphia Department of Recreation and located at Ridge Avenue and Ferry Road. Based on oral histories on the East Falls Historical Society website, there were one-hour swim sessions, and boys and girls swam on alternating days. People lined up outside the pool’s rudimentary locker room, which still stands as part of a restaurant, and a specific number of people were let in at a time. Early evenings were reserved for adults, presumably after their long days of work. Even with a limited number of swimmers at one time, the pool usually was crowded.

In the mid-1950s, the city began work on a new, vastly larger pool at Gustine Lake, near the intersection of Ridge Avenue and School House Lane (or, thinking about bodies of water, near the point where Wissahickon Creek empties into the Schuylkill River.) The natural Gustine Lake had been used since early in the 20th Century for ice skating in the winter and wading in the summer. Judging from a request from the city government in 1954 for $100,000 to purify the water in Gustine Lake[12], maintaining the lake was a challenge. The solution to this challenge was to literally replace Gustine Lake with a huge artificial swimming pool (with a bath house and, naturally, filtration equipment.) In 1958, the new pool at Gustine Lake – all two million gallons of it – opened, and the Bathey pool closed.

The pool became a nexus of racial tension between the largely white longtime residents of East Falls and the largely black residents of the Schuylkill Falls public housing project, just a long block or so from the swimming pool. Newspaper articles from the summer of 1969[13] describe sporadic fights between black and white young people near the pool as well as near the central intersection of Ridge and Midvale Avenues, and efforts by the East Falls Human Resources Committee to mediate. The Gustine Lake pool closed sometime in the late 1990’s, ostensibly owing to significant maintenance issues, leaving East Falls with no public swimming pool.

Schools and the library

Most children in East Falls attended either Thomas Mifflin public school or St. Bridget school, both located along or near Midvale Avenue, for elementary school. Children living in the Schuylkill Falls housing project attended an elementary school that was constructed as part of the overall development plan.[14] William Penn Charter School, a private school for boys, drew students from the entire Philadelphia area, and some well-off parents in East Falls enrolled their sons there. For girls, the private, Catholic-run Ravenhill Academy was a popular choice for East Falls families who could afford it. Perhaps the most notable graduate of Ravenhill was Grace Kelly.

The Falls of Schuylkill branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia was a valued resource for the community, especially for the children. Many of the oral histories on the East Falls Historical Society mention regular trips to the library as part of an East Falls childhood.

Philadelphia Textile Institute, which had been located at Broad and Pine Streets in Center City, moved to East Falls in 1951, drawing students from a wide geographic area, including some international students with specific interests in textile engineering. Enrollment at the school doubled between 1954 and 1964 and doubled again by 1978. In 1961, with enhanced accreditation, the school changed its name to Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science, and formal programs in arts and sciences and in business administration were added during the 1960’s. Initially, the campus ran along the north side of School House Lane, east of Henry Avenue, occupying land that had been owned by the Salvation Army (closest to Henry Avenue) and the Lankenau School (to the east.) In 1972, the school acquired the building and grounds of Ravenhill Academy, in one transaction roughly doubling the size of the campus.[15]

Medicine

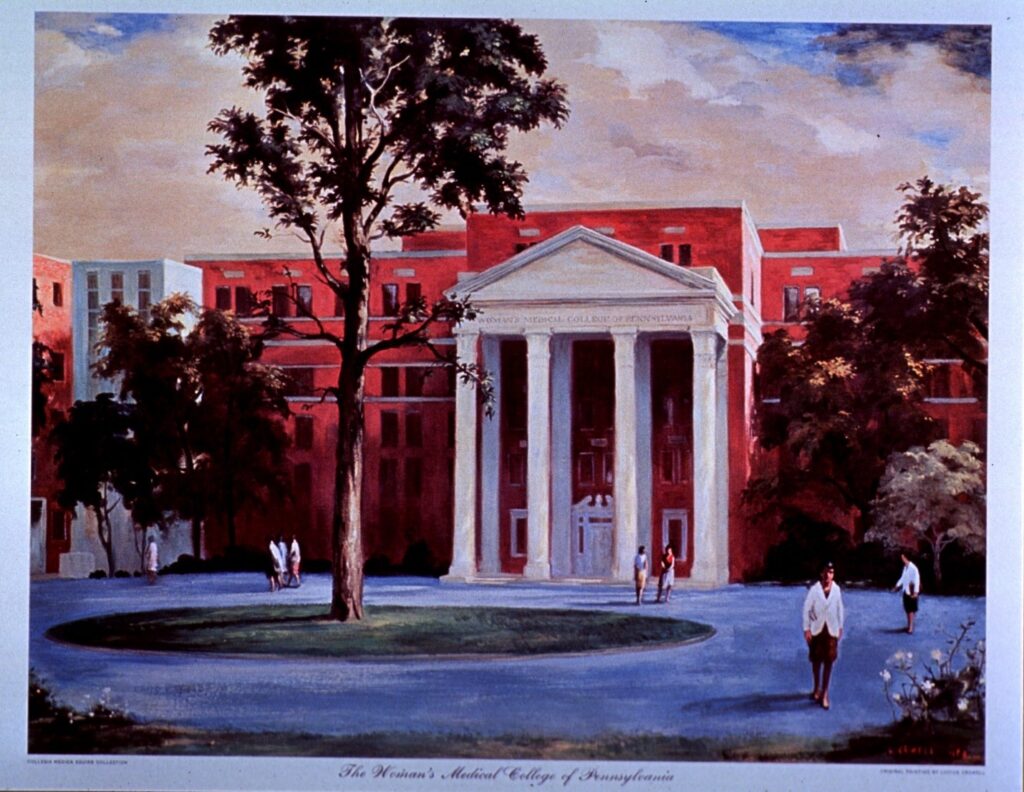

Woman’s Medical College and Hospital, which had relocated to East Falls in 1930, was the other large institutional presence in East Falls, providing health care to women and children, providing employment to many Fallsers, and of course educating hundreds of young women over the years to serve as physicians.

Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute (EPPI), a state-run institution, opened in mid-1956. As opposed to Byberry State Hospital in far Northeast Philadelphia, with a capacity of 5000 patients, EPPI was intended to be a research institution and had a capacity of only 300 beds.[16] Although EPPI was adjacent to Woman’s Medical College, the medical school (by then called Medical College of Pennsylvania) did not acquire the contract to manage it until 1981.[17]

Prominent personalities

The most prominent residents of postwar East Falls were John B. Kelly and his family. Mr. Kelly, a wealthy builder (“Kelly for Brickwork”) and an Olympic champion rower, lived in a brick home at Henry Avenue and Coulter Street. The home was (and is) across the street from McMichael Park, which he had persuaded the city to create in 1929 when he was head of the Fairmount Park Commission overseeing all city parks. Mr. Kelly and his wife Margaret (Ma) were generous patrons of local institutions that included St. Bridget Church, Old Academy Players, and Woman’s Medical College. Mr. Kelly died in 1960, and Mrs. Kelly died in 1991. Their children were prominent, as well. All three daughters – Peggy, Grace, and Lizanne – acted at Old Academy, with oral histories recalling that Grace was quiet and poised and Lizanne was possibly the better actress. Grace went on to great success in Hollywood, winning two Academy Awards in the 1950s, before retiring from acting to marry Prince Rainier of Monaco in 1956. The one son, John B. Kelly, Jr., known as Kell, was also a stellar athlete, rowing in four Olympics and winning a bronze medal for single sculls in the 1956 Games. Kell followed in his father’s footsteps by serving on the Fairmount Park Commission, and he also served as Councilman-at-Large for 12 years (1967-1979.) Kell was named to the U.S. Olympic Committee by President John F. Kennedy and served on the USOC until his sudden death in 1985.

Leon Levy, while less involved than John B. Kelly and his family in East Falls community affairs, was another prominent Fallser of the time. According to the oral history provided by his son Robert P. Levy, he owned WCAU, the radio and television stations that were then part of the CBS network. The owner of CBS, William Paley, was Levy’s father-in-law. Levy lived in the building that is now White Columns, which is now owned by Thomas Jefferson University-East Falls. His mother-in-law, Goldie Paley, lived just up Henry Avenue, in a mid-century modern home that also is now owned by Jefferson. According to Robert Levy, Leon Levy often hosted Frank Sinatra at his home, and at times Bing Crosby and other show business luminaries were guests as well.

Race relations

In contrast with swathes of North Philadelphia and West Philadelphia, there was little or no “white flight” from East Falls, even though Dobson Mills, by far the largest employer in East Falls, had gone out of business in 1927. Many Fallers were born and raised in the community, and often they moved into homes nearby when they married. There was racial tension, however. According to the oral history provided by Joe Petrone, black students were conspicuous when they first arrived at St. Bridget and Mifflin Schools. (Presumably, the public school students from Schuylkill Falls transferred into the newly built Schuylkill Falls elementary school once it opened.) As well, families living on Calumet Street, abutting Schuylkill Falls, sometimes complained of vandalism such as rocks that were apparently thrown from the Schuylkill Falls grounds through their windows. As noted earlier, the Gustine Lake swimming pool was sometimes a nexus for racial tension as well.

Economy

People in East Falls generally shopped within the community, venturing to department stores in Germantown only for special items. Owners of the many small merchants in the community generally lived nearby, and probably most of their employees did as well. The manufacturing companies that had once been the lifeblood of East Falls declined precipitously when World War II ended, and the decline persisted in the subsequent decades. As a result, East Falls necessarily became more of a commuter “suburb”, with residents leaving East Falls in the morning for jobs in Center City or the suburbs and returning in the evenings.

Industries

Before the dislocations of the Depression and World War II, the two largest employers in East Falls were Dobson Mills and the pharmaceutical company Powers & Weightman. Many of the employees lived nearby in East Falls and walked to work. The business of Dobson Mills simply closed down in 1927. In that same year, the company then called Powers-Weightman-Rosengarten was acquired by its competitor Merck, which rapidly discontinued operations at its site in East Falls.

Despite these major losses, many industries that were active within the boundaries of East Falls during World War II. Fred. Whitaker Co. and Mayfair Plush Company occupied most of the Dobson buildings south of Scotts Lane. One Fallser recalls getting a job in 1945 with a company called Vander Beck, a hosiery mill that also occupied space somewhere in the former Dobson’s Mills.[18] On the eastern edge of East Falls, abutting Wissahickon Avenue, there were large installations of the U.S. Army Signal Corps and the Bendix Corporation. Along the southern edge of East Falls were Budd Manufacturing Company, Midvale Steel, Sinclair Refining, Nicetown Manufacturing, Taylor Davis Iron Works, Philadelphia Lawn Mower Manufacturing Company, the American Pulley Company, Nice Ball Bearing, Tasty Baking Corporation and Rayburn Manufacturing Company. Along Indian Queen Lane in the heart of East Falls were Hohenadel Brewery and American Steel Engraving company. Most of these closed or significantly contracted in the postwar decades.

Local shopping and services

(Include “gasoline alley” on Midvale Avenue)

Commuting and public transit

While many Fallsers continued to work in or near East Falls, an increasing number were commuting to the redeveloping environs of Center City or to the increasingly developed suburbs. The commutes into Center City were facilitated by two commuter train stations convenient to East Falls – the East Falls station on the Reading Railroad, and the Queen Lane Station (just across the informal boundary of Wissahickon Avenue) on the Pennsylvania Railroad. The former was more convenient for the historic core of East Falls, while the latter was more convenient for residents of so-called “Queen Lane Manor,” where lands were subdivided for residences primarily in the 1920s and 1930s. For drivers, East River Drive afforded a short, scenic route to the northwest edge of Center City, just a few blocks from the office buildings of the newly developed Penn Center.

Within East Falls, the 62 trolley line ran up Midvale Avenue and provided access to the shopping resources of Germantown. Bus lines crisscrossed the neighborhood, as well.

The built environment

By the end of World War II, the heart of East Falls had been almost completely built out. From Allegheny Avenue to the Wissahickon Creek, up to and beyond the Reading Railroad tracks, there were only two large tracts of land not in use – the remains of Dobson Mills and the Powers-Weightman-Rosengarten plant. The latter site became a public housing project by the mid-1950’s, but Dobson Mills remained largely abandoned until the late 1990’s. Other development took place close to the peripheries of East Falls.

Highway construction

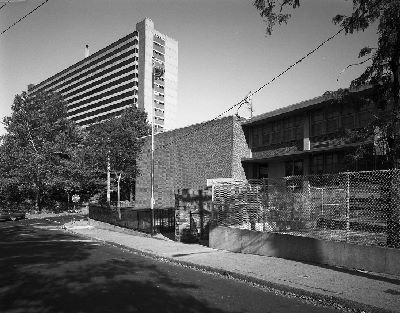

The Roosevelt Expressway was, for highway engineers, a logical way to connect Northeast Philadelphia with the then-new Schuylkill Expressway. A Philadelphia Inquirer article on February 28, 1958, reported that the budget for the expressway, from 9th Street and Roosevelt Boulevard to the Schuylkill Expressway, was precisely $6,001,000. The cost, unsurprisingly, ballooned to some $25,000,000, according to the Inquirer.[19] . Construction of the highway, which opened in the Spring of 1961, created some notable physical and social changes to East Falls. The Roosevelt Expressway took a chunk of McDevitt Playground and a fragment of the former Dobson Mills property, eliminated Crawford Street from the Reading Railroad tracks down to its former terminus at Ridge Avenue, created a deep highway trench between the campuses of East Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute and Woman’s Medical College, eliminated the unoccupied lower block of Krail Street, and essentially paved over the former site of the Breck School, which had once been the public elementary school for the community. The physical gash across what had historically been considered East Falls further isolated several residential blocks flanking Allegheny Avenue from Henry to Ridge Avenues, the historic St. James the Less Church, as well as industries and two cemeteries along Ridge Avenue south of the former Dobson Mills. The historical record is silent about the community response to this radical transformation of East Falls, or even whether there was any organized effort to elicit community response.

Public housing

The recently built Abbottsford Homes on lower Henry Avenue, designated as “United States Defense Housing” on the 1942 WPA land use map, housed workers at the many nearby industries that were doing defense work. The project comprised 700 units designed to hold precisely 2603 residents. Abbottsford Homes occupied what had been the grounds of Bella Vista, the home of Bessie Dobson Altemus, the first of several government acquisitions of land owned by the family of the erstwhile Dobson Mills. Abbottsford Homes transitioned to become housing for veterans shortly after the war. In the early 1950’s, as part of a Federal government program, Abbottsford was taken over by the Philadelphia Housing Authority as housing for people in poverty. Families who did not meet the income criteria for PHA housing had to leave, and PHA tenants replaced them.

The PHA housing portfolio in East Falls roughly doubled when the Schuylkill Falls housing project opened in late 1954. The project was designed by Oscar Storonov, a prominent Philadelphia architect whose other credits included collaborating on the nationally lauded Society Hill redevelopment plan as well as the design of Hopkinson House on Washington Square.[20] On 27 acres east of Ridge Avenue formerly occupied by Merck & Co. worker housing and manufacturing facilities, the Schuylkill Falls project comprised 714 units – 448 of them in two 15-story towers, and the other 266 in rowhouses and so-called hillside buildings.[21] In 1954, an onsite elementary school called East Falls Elementary School opened.[22]

Private housing

There was little vacant land for new private housing in the heart of the community. However, a plot of land known informally as McCarthy Field near Cresson Street and Merrick Road became the site of the so-called “New Houses,” about 140 brick row houses built roughly between 1945 and 1955.[23] At one time, this plot of land had been owned by descendants of John Powers, one of the founders of Powers & Weightman.

While the “new houses” were visually similar to a host of postwar brick row houses built throughout the city, a cluster of houses in the distinctive “mid-century modern” style was built mostly during the 1950s by subdividing an estate north of School House Lane, once owned by a man named David Milne. The houses occupy lots on the single block of Apalogen Road (the 41XX block), lots along the west side of 41XX Timber Lane, and two or three lots on the adjacent 34XX block of West School House Lane. Each house was designed individually, so a number of architects were involved. Four of the structures were designed by Norman Rice, a locally prominent architect who was a student and protégé of the esteemed Louis Kahn. One of the first licensed architects in the country, Elizabeth Fleischer, designed another house in the group. Another mid-century modern home, designed by Richard Neutra, an internationally prominent Austrian-American architect, is a few hundred yards east of this area. It sits along Cherry Lane, a modest path into the woods running off School House Lane, and is currently owned by Thomas Jefferson University-East Falls.

[1] Weigley, RF et al. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 650. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1982.

[2] Corrupt and Contented – Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (philadelphiaencyclopedia.org)

[3] Weigly, RF et al., op. cit., pp. 651-655

[4] Penn Center – Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (philadelphiaencyclopedia.org)

[5] Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) (phillyroads.com)

[6] Oral Histories (eastfallshistoricalsociety.org)

[7] Comprehensive-Plan-1960.pdf (phila.gov)

[8] PhilaGeoHistory Maps Viewer

[9] Oral history with David McClenahan

[10] Alden Theater in Philadelphia, PA – Cinema Treasures

[11] Harry S. McDevitt Playground | Philadelphia Parks & Recreation Finder

[12] Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1954, p. 33

[13] For instance, Philadelphia Inquirer, August 14, 1969, p. 67

[14] PUBLIC HOUSING (state.pa.us)

[15] History | Jefferson Online (formerly PhilaU Online)

[16] Philadelphia Inquirer, May 17, 1956, page 9

[17] Peitzman, SJ. A New and Untried Course, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2000, pp. 234-235.

[18] Oral history with Jack McNicholas

[19] Philadelphia Inquirer, February 28, 1958; and May 20, 1961

[20] 02 Mar 1952, Page 58 – The Philadelphia Inquirer at Newspapers.com

[21] 26 Sep 1954, Page 26 – The Philadelphia Inquirer at Newspapers.com

[22] Philadelphia Inquirer, May 20, 1956, page 107

[23] atlas.phila.gov